Lately I’ve been getting back to looking at shot and point distribution charts, ones of players still in the Finals and a few other greats over their entire careers. The charts are the ones I’ve used for players and teams in previous posts, tracking shots on NBA.com from the restricted area, in the paint non-restricted area, mid-range, corner 3, above the break 3, and free throws, but I’ve recently added a few more charts to the mix. This post is basically a trial version of them with Ray Allen’s being the ones tested, and if it turns out all right I might turn it into a blog series over the off-season.

There will probably be some tweaking to do, but for now I plucked Allen’s yearly numbers from NBA.com which somehow has shooting stats and charts starting not at 2001 but 1997, though I don’t consider the ones from ’97 to be all that accurate thanks to the shortened three-point line back then. We get to work with every other season of Allen’s career, though, and maybe other notable players from the late-90s to today.

In past posts, I included GIFs and/or screenshots to show changes in charts from each season, player or team, and while I’ll use each of those for this post I’ll also use galleries so readers can cycle through charts at their own pace. The galleries also provide a little animation between each season to help show shifts in shooting and scoring.

Hopefully all of that isn’t confusing, but I can be pretty lazy with explaining things. For those who haven’t looked at these kinds of charts before, maybe just looking at them is easier to understand anyway.

Allen’s attempts over his career from both the field and the free throw line were what I looked at first, and below is an example of the four different charts I made for that section. This one is from 1998’s available stats:

My apologies if screenshots look a bit blurry. They look much sharper when clicking to enlarge.

The first 3 charts are mostly similar with FGA distribution missing free throws, of course, but that one and attempts per 36 minutes compliment Allen’s first chart (attempts per game) best in his later years when his minutes and total attempts decline.

The last chart, attempts per 36 minutes compared to the player average, is something I’ve recently been playing with, though it doesn’t adjust for pace. In 1998, Allen took nearly six mid-range shots per 36 minutes, but compared to every other player’s numbers it was more standard than his attempts from the corner three, where he took twice as many attempts/36 minutes as the average player. This is a pretty common theme over Allen’s career.

Below are the rest of Allen’s attempts in a photo gallery. It should be on auto play, so I guess in way it’s still a slow-moving GIF, but it can be paused any time:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Where Allen shoots from each location has obviously changed over the years, once heavy on mid-range shots and almost always making a ton of either above the break threes or corner threes compared to the player average.

Below are the differences between his second and 18th season of his career (1998 and 2014):

Allen still takes a similar amount of above the break threes per 36 minutes as he did in 1998, but now he attempts about 3.5 times as many corner threes, half the free throws and shots in the paint (outside the restricted area), a third from mid-range, and about three-fifths as many around the rim. It also shows how three-happy the league has become with Allen’s above the break 3s/36 minutes more standard now than compared to the late-90s.

Some of Allen’s changes are consistent with how his FGA distribution has changed with each team. Below is a GIF putting his combined point distributions for each team together (click to enlarge):

Along with the roster around him, age most likely contributes to Allen’s shift in FGA and FGM distribution. With the Heat, it also changes a bit when he’s in lineups with or without LeBron James:

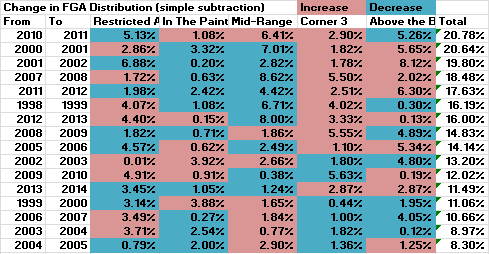

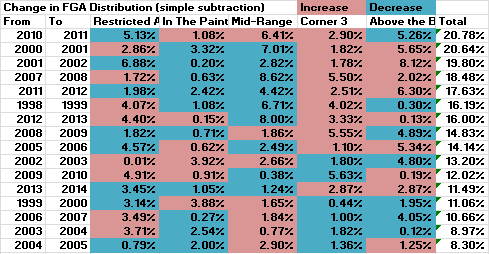

I also looked at Allen’s biggest changes in FGA distribution from season to season, basically by a simple subtraction of percentages. I took 1998’s percentages and subtracting them from 1999’s, for example, then made every change in percentage positive and adding each location’s numbers up.

This is what each season looks like, sorted by biggest total changes to smallest:

Visually, that looks correct when looking how the largest and smallest changes stack up (as usual, click to enlarge if you’d like):

Allen took more of his attempts from mid-range in 2011 despite having a fourth straight decline in usage rate, but he also took a higher percentage of his attempts from the corner three and, as shown much further down in this post, he was way more accurate there than in 2010.

Mid-range and non-restricted area paint attempts are the biggest differences in 2004 and 2005, but everything else looks the same otherwise. When comparing changes in Allen’s FGA distribution in 2003 before and after the trade that sent him from Milwaukee to Seattle, his chart hardly moves and would be the lowest compared to season-by-season changes, totaling to a 6.53% change. (Threes were a different story. More on that later.)

Simply subtracting doesn’t take into account the shots Allen takes least (depending on the season, either corner threes or in the paint non-RA shots) and most (either shots around the rim or above the break threes). It’s often a bigger deal if a player or team takes five percent more of field goal attempts from the corners than around the rim, and I tried a couple ways to balance for that but hit snags since they’d be hopeless if Allen (or any other player, or team) took zero percent of their shots from one of the five locations. Also, I’m terrible at math and maybe over-thought the whole process, so if there’s an easy way to calculate that stuff I’d love to hear it since I’m looking into shooting and scoring by teams over each season, among other post ideas.

To go back to mid-range and other two-point shots, though, it may or may not be surprising that Allen took as many as he once did, though that can be said about the league as a whole. Mid-range shots made up a great chunk of Allen’s shots for a long time, and about 20 percent of his attempts as a member of the Heat still come from that area of the floor, but that’s down from what was anywhere from 25 to over 40 percent as a Buck, Sonic, or Celtic.

Looking at his shot charts at NBA.com that split into several locations, less of his twos come from the wings now than they did as a Sonic or Celtic, but there’s still a similar amount from the baseline where, for most of his career, Allen took the most of his jump shooting twos.

Below is a breakdown of Allen’s 2PA distribution according to spots on NBA.com’s shot charts. I gave locations names that are hopefully self-explanatory, but can be found here just in case:

As usual, click to enlarge. Very helpful!

Allen’s baseline shots are the standard ones from being run off the three-point line and getting separation off screens, but quite a few come from trying to get space off the dribble when the shot clock is winding down. He doesn’t get all that far, painful to watch when he was once so good at attacking off the dribble (one example here), but he doesn’t need much space to get his beautiful shot off anyway.

Even if Allen seems to struggle a bit more in getting to the rim off the dribble, he’s still having career-lows or near career-lows in attempts/36 minutes from all the 2PA locations on NBA.com’s shot charts all while having a career-high in corner three-point attempts/36 minutes and percent of his FGA being corner threes. His mid-range shots/36 minutes have gone from around or above league-average in his first 15 charted seasons to two-thirds and nearly half the average in 2013 and 2014, respectively, and he shot nearly three times as many corner threes per 36 minutes as the average player this season. The leaders from the corners each season often take four to five times as many as the average player, though, sometimes even more when looking 10+ seasons back. James Jones led all players this year by taking 5.8x corner threes/36 minutes, but in 2005 Donyell Marshall took 7.1 times as many, then followed it up with 6.0x and 5.8x as many while Cleveland in 2006 and 2007, respectively. Fun times.

To touch on free throws, Allen’s charts almost always show him above the player average in free throw attempts/36 minutes during his prime which, like his attack off the dribble, feels underrated considering his status as a killer shooter.

I found his free throw and three point rates to be pretty interesting, even though they seem common in both his age and that when the free throws lower the threes often rise:

I’ll touch more on threes later when chiming in on some thoughts on Allen’s scoring distribution, which I looked at in a similar way to shot attempts but with some tweaks. Below is a gallery visualizing four scoring stats from 1998 to 2014, but with some changes in charts from attempt distribution:

- Points per game from the six spots on the floor.

- Effective field goal percentage from all but free throws.

- Point distribution but this time including free throws, unlike in the first gallery of graphs.

- How Allen’s points/36 minutes from each spot measure up with the league average (per player).

Anyway, flip through the charts if you’d like:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

There are some hopefully cool things to look at. Going back to mid-range shots, below is a similar graph like before but covering 2PM distribution:

And a gallery comparing 2PA and 2PM distribution. Flip flop if you’d like:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Season by season, Allen’s changes in point distribution from largest to smallest are a bit different from changes in FGA distribution, where the largest for that was from 2010 to 2011 and the smallest from 2004 to 2005:

Understandably, the smallest change in point distribution was in Allen’s second season with the Heat. The largest change was not after a trade in 2003 or 2007 or going from the Celtics to the Heat in the summer of 2012, but from his seasons as a Buck in 2001 and 2002.

Again, with simple subtraction, that all looks correct visually:

From 2001 to 2002, Allen scored less from the free throw line but upped his three point rate from .357 to .460. He took 3.67 times the average player’s corner 3s/36 minutes, ranking tenth minimum 1,000 minutes. For above the break threes (he attempted 3.32x the player average), he was only behind Antoine Walker (3.64), Jason Williams (3.70), and Tim Hardaway (4.22).

No shame in falling just behind those three players in anything related to threes, and Allen’s got pretty nuts when flipping through the 1998-2003 section of the scoring gallery shown above. Maybe suspected from the 2002 charts: Allen placed in the top 10 that season in both threes attempted and made for both the corner and above the break three. It started a string of top 10 finishes in the latter location:

I thought Allen’s threes deserved a gallery of multiple charts, featuring both three-point attempt and made distribution from the five spots available on NBA.com’s shooting charts, another with accuracy from those locations, and a line chart tracking the shooting swings each season.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

1998, 2002, and 2010 look almost perfectly balanced in attempt distribution from each spot, while some weirdly (for a right-handed shooter, anyway) show a great deal of threes from the right wing. Also, to go back to the graph of his shots with and without LeBron on the floor, it’s no surprise to see Allen taking more of his threes from the corner as a member of the Heat. Last year he teed off from the left side, but this year it’s from the right. Attempts from straight away are just about gone and weren’t ever a big deal anyway.

Below is a GIF of Allen’s combined distributions during his Buck, Sonic, Celtic, and current Heat career. The differences in attempted and made threes are pretty minor (click to enlarge):

Followed by that GIF are threes in 2003 before and after the trade that sent him from Milwaukee to Seattle. Quite a change midway through the season:

Again, it’s kind of weird to see a right-handed shooter take a bunch of his attempts from the right wing, but Allen went through shifts from just about everywhere but from straight away. Shots from the corners and from straight on barely changed, at least in attempt distribution.

Lastly, Allen’s assist percentage on threes over the last two seasons are some of his highest ever. Among other notes, the right corner was a flat 100 percent for six straight seasons with 114 assisted threes during that stretch:

Allen’s long been one of my favorites to watch from the times his NBA Live ’98 player torched me to how unfair he can make Miami’s offense just by standing in a corner. His charts were a test to see how they look in a blog post and if readers would be curious about ones for other players. A lot of other greats over the years have some cool charts, or maybe I’m biased because I was so curious about them to begin with. Probably the latter.

Some other thoughts:

- I could’ve added playoff shooting and scoring, but was worried it would clutter this post even more.

- Clutter…were there too many charts? A lot of them were player dependent, though. As much as I’d like to, I’d probably refrain from 3pt charts for someone like Tim Duncan. Maybe throw in a game of Solitaire instead.

- The charts obviously don’t tell everything, like I can’t even put together SportVU-related shooting charts because the numbers don’t add up to Allen’s total points. I could try fooling around with them for other players, though, and see if something’s presentable.

Oh well. Curious what others think of this post and if any tweaks could’ve been made. This is definitely a trial version of posts I had in mind for other players and was also a post meant to shake off a ton of rust over the last few weeks.